2018 Culinary Class:

Oyster 101

At our first installment of the 2018 Culinary Class Series, Jess Cagle from ICO Farm was on-site to lead the Oyster 101 seminar & tasting.

ICO: Oyster 101 Fundamentals

Where do oysters come from?

In the wild, an oyster starts as an larvae with a simple eye that only sees light and dark. It swirls around in the open ocean for up to a month, looking for a safe place to land. Most often it will land in the sand and get buried, or swept out to sea, or eaten for lunch by an unsuspecting sea creature.

Best case, it finds a hard rock, shell or reef to attach to. Once there, that will be the oysters home for life, no opportunity for do- overs. Chances are, it will soon be joined by other oyster babies looking for a safe place to land. Those oysters will then spend the rest of their lives competing with their neighbors for food and nutrients.

You can always spot a wild oyster at a raw bar, the shell will be their tell. Because they can be forced to compete for space, their shells sometimes grow in erratic directions.

Farm v. Wild

We all know the wrinkled up face people make when you mention farmed Salmon— is it the same with oysters? Not even close.

If you are a farmed oyster, you were likely grown from seed procured from a hatchery where a spawn was controlled and that larvae was given a safe place to land, and ideal growing conditions for the first past of its life.

Farmers will then ‘plant’ the babies giving them the best possible chance for survival. Where in some cases they grow right alongside a wild population.

Five Oyster Species

Eastern or Crassostea Virginica: Everything on the East Coast from PEI down to the gulf. Known for their salt!

Pacific or Crossostrea Gigas: Found on the West Coast and Europe. Known for their craggy shell and mineral flavors.

Kumamoto: Originally from Japan, now farmed on the west Coast. Everyone’s favorite, strong cucumber and melon flavors.

Olympia: The only oyster indigenous to the West Coast. Small, rare, and incredibly slow growing. Flavors of copper and smoke.

European Flat or Belon: Originally from the Brittany region of France, now found in wild populations in Maine. Rare, and coveted by a cult following. Intense copper and iodine flavors that really stick with you.

Kumamoto, Belon, Eastern Virginica (Island Creek Oysters), Pacific Gigas (Blue Pools), Olympia

Merrior

We talk about merrior with oysters the same way we talk about terrior with wine. There are certain environmental conditions that really impact the oyster, making it truly unique. These include but are not limited to temperature of the water, salinity of the water, proximity to land, nearby brackish flow, and hand of the grower.

Common Grow Out Methods

Bottom Planted: This is how Island Creeks spend the last year or so of their life! Requires specific conditions to grow oysters in this way, as they are exposed to all elements, at all times. The sand must be firm, predators must be scarce, and the threat of ice must be relatively low. Growing oysters directly on the bottom tend to grow a thicker shell as a result of being tossed around by the natural currents of the ocean. Bottom planting also tends to produce a rounder oyster, as they have more room to grow. They are free range!

Rack & Bag: Oysters of like sizes are paced in plastic mesh bags and slid into cages or laid on top of the racks themselves. This will keep the oysters elevated off a potentially soft bottom when the oysters could be buried, causing them to suffocate and die. This method ensures potentially higher returns but does limit capacity just based on the equipment required. In most cases, most of this gear will need to be removed in the winter because of the threat of ice. Poses a challenge for year-round harvesting.

Trays: Like rack and bag, growing in trays will keep the oysters off the bottom, protecting them from predation. The major difference between the two is that the oysters are directly in the trays. Densities must be monitored to ensure as the oysters grow, they are redistributed to keep from overcrowding. Overcrowding will cause the shells to be weak and misshapen and can also cause death.

Tumbling or Floating Baskets: Typically used when growing oysters near the surface of the water. Oysters are placed in baskets or bags that are attached to a long horizontal line. These bags will get tossed around in the surf, causing the oyster shells to chip off against one another, forcing them to grow back stronger. Great for areas with much of a threat of ice.

Environmental Benefits: Why are oysters so great?

Quite plainly, oysters are good for water quality. They are filter feeders that use their gills and cilia to suck in water from their closely parted shells. Oysters extract excess nitrogen from the water and use it to build their shells. By removing the nitrogen they are preventing algae blooms. These algae blooms keep the sun from reaching

the sea floor, so by eliminating those, the flora and fauna will have the opportunity to flourish. When the eelgrass grows, other sea species move in creating a sustainable environment for all.

A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day. As the story goes, it would take the oyster population of Duxbury bay only 9 days to clean all the water in the bay.

Oysters eat only what is in the water, farmers are not adding anything to that water. There is no waste.

Eating and Talking

Appearance: Pick up the oyster, what do you see? Take note of the shell weight and apparent strength. Are there any distinguishing characteristics? The meat should be plump and opaque, is it?

Smell: Smell is a big part of the experience, you smell your wine, don’t you? Some farmers will swear that they can smell the bay just on their oyster alone.

Texture: Firm, soft? What are you sensing from that first bite?

Chewy Chew: Do you taste salt, cream? How’s the salinity? Low or high? Are their sea veggie flavors? Is the oyster more savory like chicken broth?

Down the Hatch: What lingering flavors are you left with?

Helpful Terms to Know

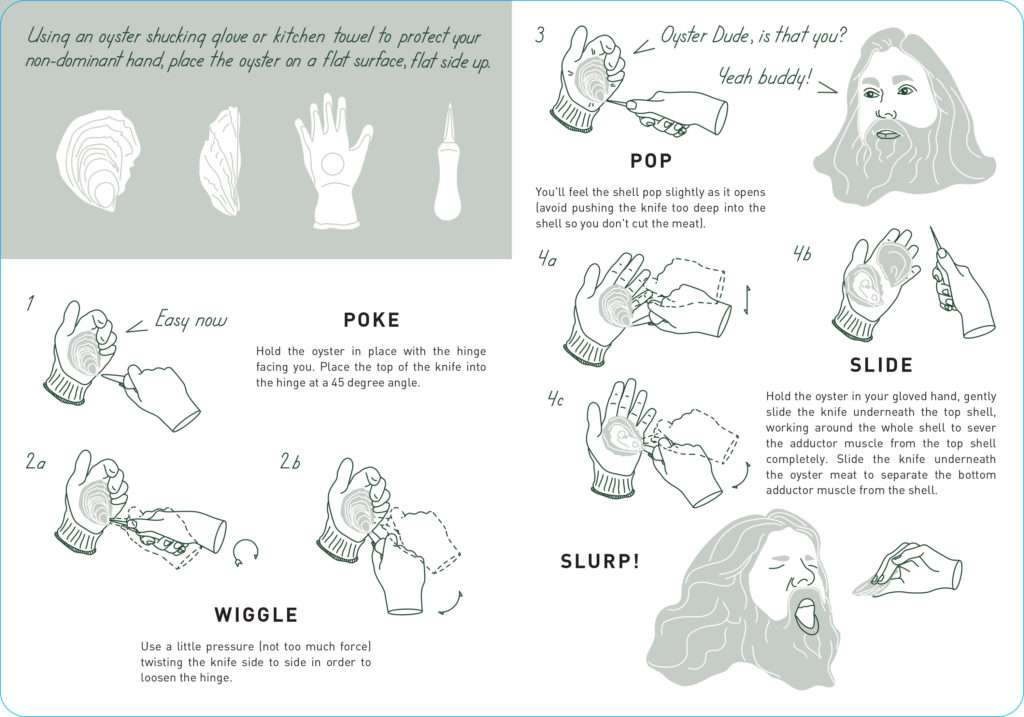

Adductor: The adductor is the muscle that holds the oyster shut. Chewy, clam-like texture.

Cultch: Cultch is ground up shell that can be spread along the ocean floor to allow free-floating oyster larvae looking for a home, something to attach to.

Cull: Culling is the act of sorting oysters by size.

Dredge: A rake-like object that is towed behind a boat the scoop oysters off the bay floor.

Flats: Refers to the tidal flats, areas exposed at low tide

Glycogen: The ‘fat’ in the oyster, responsible for what can sometimes be called the ‘roundness’ of the oysters flavor— the dairy quality.

Grants/Leases: When we refer to a specific farmers lease or grant, we are referring to the bottomland he or she has been allotted on which to grow their oysters.

Hinge: The hinge is point where the two halves of the shell meet. Serves as the most common entry point for a shucking knife.

Intertidal: The zone between the high and low tide mark. Oysters grown in an intertidal zone would commonly be exposed to air at low tide.

Mantle: See diagram! The darker ring around the outside of the oyster meat. The organ that actually secretes the shell.

Midden: Huge shell piles of discarded oysters. They dot the coasts in places where native peoples and early settlers relied on wild oyster populations as a source of protein.

Oysterplex: Quite literally, the heart of Island Creek. This is the little shack out of the bay where the oysters are ‘count, wash, bagged’ and prepared for their journey to their new homes.

Porn Stars: A special cull of Island Creeks only for our 3rd most important client—Thomas Keller of Per Se and French Laundry

RTG: Return To Grant, meaning oysters that are misshapen or have a nick in their shell, or too small to sell get returned to the water to grow and self-repair. These will be hauled up later in the season or next and be beautiful oysters!

Regs and Selects: Regs are 3” inch oysters; Selects are also called Petites, and clock in at 2” to 3”. In Massachusetts, it is not legal to sell oysters within the state that are sub 3”.

Spat: Tiny oysters that have just attached themselves to a hard surface are called spat.

Spawning: When an oyster spawns, it releases sperm and egg into the water.